GIỚI THIỆU SÁCH MỚI

Văn Nghệ Biển Khơi trân trọng giới thiệu:

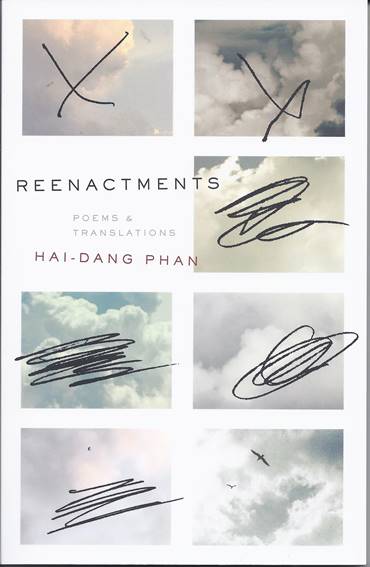

Reenactments

(Phôi Dựng)

Thơ Tuyển của Phan Hải Đăng

Nhà Xuất Bản Sarabande Books, 2019,

100 trang, 42 bài thơ

In Reenactments, Hai-Dang Phan grapples with the history, memory, and legacy of the Vietnam War from his vantage point as the son of Vietnamese refugees. Through a kaleidoscope of poetic forms, the past and present, the remembered and imagined, all intersect at shifting angles providing urgent perspectives on conflicts both private and public. Phan weaves throughout the collection stories of his family’s exodus from Vietnam, thoughtfully reenacting an American experience of immigration, dislocation, inheritance, and hope. And, in a fresh move, Phan widens the lens, incorporating translations of several Vietnamese poets. This moving debut marks a vital addition to the literature of immigration and a distinctive contribution to contemporary poetry.

Trong Phôi Dựng, Phan Hải Đăng quần thảo với lịch sử, ký ức và di sản chiến tranh Việt Nam từ quan điểm thuận lợi là một đứa con của người tị nạn Việt Nam. Qua lăng kính vạn hoa của khuôn bản thi ca, quá khứ và hiện tại, tưởng nhớ và tưởng tượng, tất cả giao tiếp ở nhiều góc độ biến dạng gây nền cho các nhận thức cấp bách về xung đột của cá nhân cũng như cộng đồng. Phan đan kết những mẩu chuyện sống của gia đình anh trong chuyến di tản khỏi Việt Nam, phôi dựng lại rất chu đáo kinh nghiệm của một người di dân Mỹ về nhập cư, phân tán, di sản và hy vọng. Và, trong một nổ lực mới mẻ, Phan mở rộng lăng kính, kết hợp các bản dịch của một số nhà thơ Việt Nam. Sự ra mắt cảm động này đánh dấu một sự bổ sung quan trọng cho nền văn học nhập cư cũng như đóng góp đặc biệt cho thi ca đương đại.

(Vũ Hoàng Thư phỏng dịch)

oOo

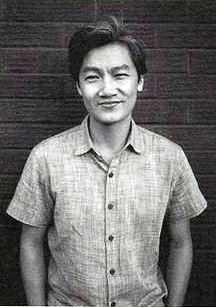

HAI-DANG PHAN was born in Vietnam in 1980 and grew up in Wisconsin. His work has appeared in the New Yorker, Poetry, Best American Poetry 2016, and the chapbook Small Wars. He is the recipient of a National Endowment for the Arts Literature Fellowship, the Frederick Bock Prize from Poetry, and the New England Review Award for Emerging Writers. He currently teaches at Grinnell College and lives in Iowa City, Iowa. Reenactments is his first book.

“In poems that are as intense as they are lucid, Hai-Dang Phan illustrates James Baldwins assertion that history is not the past, it is the present. The military hardware transported on the interstate, the vexing public memorials for past and recent wars, the refugees on the TV news, and the punk band named after the Viet Cong—Phan shows the present charged by the toxic continuing of the past. Reenactments is a book of haunted, forensic reckoning. Each poem in this beautiful and bitter book may begin in the intimate stories of the personal, but its ultimate scope is the national story of the broken American self and the havoc of its imperial project.” — RICK BAROT

“Throughout this wonderful debut, we experience the various modes of reenactment: as memory, as mimesis, as fugue state, as cinema, and as translation. American English can no more turn away from what its Vietnamese citizens speak: ‘I heard America burp.’ Hai-Dang Phan, obsessed as he might be with the tenderness of survival and the transmogrification of war weapons, cannot forget that to be Vietnamese is also to remember Iraq and Syria. This book is greater than the interiority of family. It builds rooms in its stories to house more and more people.” — FADDY JOUDAH

“Haunted by the long aftermath of war and diaspora, Hai-Dang Phan’s poems and translations explore how memory, like language, is never static. Moving from war reenactments to familial narratives to memories of Vietnam, Phan’s language is pliable, attentive to terror, humor, sorrow, and hope. His gaze is clear-eyed and expansive. Reenactments is a gorgeously crafted, deeply moving, and singular debut.”—EDUARDO CORRAL

“This must be the best poetry: the kind that makes you feel that you ought to appreciate your life, then change it, and urgently. Hai-Dang Phan writes what needs to be written, translates what we need to understand, and reminds me to love as much as I said I did. Reenactments deserves to go not just far, but beyond.”—TARFIA FAIZULLAH

Thơ trích từ Reenactment

ARRIVALS AND DEPARTURES

A passenger plane roars above us

like a password confessed in the sky.

I look down and around me—

impossible tangle of wires like knots of black hair,

streets bare and broken,

river choked with garbage,

the pastel buildings beside themselves

—when my cousin V. says

this must feel like flying.

We’re standing on a second-floor balcony.

He must be imagining

patches of dead grass as lush green rice fields,

the only country he’s ever known

dissolving in a solution of night.

I spot a stray dog.

It follows a memory to the corner

and lifts a hind leg into the air.

BLACKOUT

in memory of Tran Thi Thu

The subzero weather and cryogenic freeze

of your bedroom is your last bid at immortality.

The air conditioner produces an arctic breeze

in this corner of Ho Chi Minh City.

Like a sunbather on a ocean liner,

you doze on the throne of your folding chair.

Arrayed on a tray are “Western” painkillers,

sleeping pills, and black dye lor your hair.

I sit beside you, grandson and honorary guest.

Korean soaps play on the television all day,

prepaid for your voluntary house arrest,

dubbed so you can understand what they say.

The karaoker next door stops midcroon—

the electricity has been cut

for the blackout on Monday afternoons.

I fan you so you don’t melt.

Your life stretches across three wars.

Your mother was slain by bandits near the village

where you were born. You disobeyed your father

and fell in love with a poet at a young age—

the one who went north for the August Revolution,

who called on fall to block the coming spring.

This romantic version is your historical revision.

Your name means autumn.

You were married off that spring.

MY FATHER’S NORTON

INTRODUCTION TO LITERATURE, THIRD EDITION (1981)

Certain words give him trouble: cannibals, puzzles, sob,

bosom, martyr, deteriorate, shake, astonishes, vexed, ode...

These he looks up and studiously annotates in Vietnamese.

Ravish means cướp đoạt; shits is like when you have to đi ỉa-,

mourners are those whom we say are full of buồn rầu.

For “even the like precurse of feared events” think báo trước.

Its thin translucent pages are webbed with his marginalia,

graphite ghosts of a living hand, and the notes often sound

just like him: “All depend on how look at thing,” he pencils

after “I first surmised the Horses’ Heads / Were toward Eternity—“

His slanted handwriting is generally small, but firm and clear.

His pencil is a No. 2, his preferred Hi-Liter, arctic blue.

I can see my father trying out the tools of literary analysis.

He identifies the “turning point” of “The Short and Happy Life

of Francis Macomber”; underlines the simile in “Both the old man

and the child stared ahead as if they were awaiting an apparition.”

My father, as he reads, continues to notice relevant passages

and to register significant reactions, but increasingly sorts out

his ideas in English, shaking off those Vietnamese glosses.

1981 was the same year we vượt biển and came to America,

where my father took Intro Lit (“for fun”), Comp Sci (“for job”).

“Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening,” he murmurs

something about the “dark side of life how awful it can be”

as I begin to track silence and signal to a cold source.

Reading Ransom’s “Bells for John Whiteside’s Daughter,”

a poem about a “young girl’s death,” as my father notes,

how could he not have been “vexed at her brown study /

Lying so primly propped,” since he never properly observed

(I realize this just now) his own daughter’s wake.

Lấy làm ngạc nhiên về is what it means to be astonished.

Her name was Đông Xưa, Ancient Winter, but at home she’s Bebe.

“There was such speed in her little body, I And such lightness

in her footfall, / It is no wonder her brown study / Astonishes

us all.” In the photo of her that hangs in my parents’ house

she is always fourteen months old and staring into the future.

In “reeducation camp” he had to believe she was alive

because my mother on visits “took arms against her shadow.”

Did the memory of those days sweep over him like a leaf storm

from the pages of a forgotten autumn? Lost in the margins,

I’m reading the way I discourage my students from reading.

But this is “how we deal with death,” his black pen replies.

Assume there is a reason for everything, instructs a green asterisk.

Then between pp. 896-97, opened to Stevens’s “Sunday Morning,”

I pick out a newspaper clipping, small as a stamp, an old listing

from the 404-Employment Opps State of Minnesota, and read:

For current job opportunities dial (612) 297-3180. Answered 24 hrs.

When I dial, the automated female voice on the other end

informs me I have reached a nonworking number.

QUIET AMERICANS

Kinnic and Mom in Da Nang,

us in a frozen dinner aisle in River Falls.

*

Spooning our chicken vindaloo

we watch Mankiewiczs The Quiet American

on Turner Classic Movies,

something my father and I can agree on.

*

In a ditch near the watchtower

a Fiat bursts into a signal fire.

*

We aren’t interested in the love

triangle or whodunit, but are spellbound

by old Saigon flickering in the rear window,

shadows of rue Catinet.

*

Snow puts the night on mute.

We know how it ends.

SAIGON NOTEBOOK

First stop, the Van Hanh Buddhist University.

After a short meditation

the student monks race out of the hall

to catch the second half of a football match:

nil-nil on the green pitch of mindfulness.

*

Next attraction on the trauma tour,

site of Thich Quang Diic,

the burning monk—I see nothing but dust,

a blur of bodies rushing in and out

of the street, sun igniting the horizon.

*

According to the vendors at Ben Thanh Market,

the dead prefer US dollars to burn,

a paper Benz or Beamer, counterfeit

passports, fake plastic fruit and flowers.

In this, they resemble the living.

*

At New Noodle Heaven, my cousin and I slurp

our steaming bowls of soup, and stare

at new customers whose bedraggled uniforms,

shovels, and trumpets tell us they are fresh

from chanting mourning songs and digging graves.